Jennie R. Dobois: The Discovery

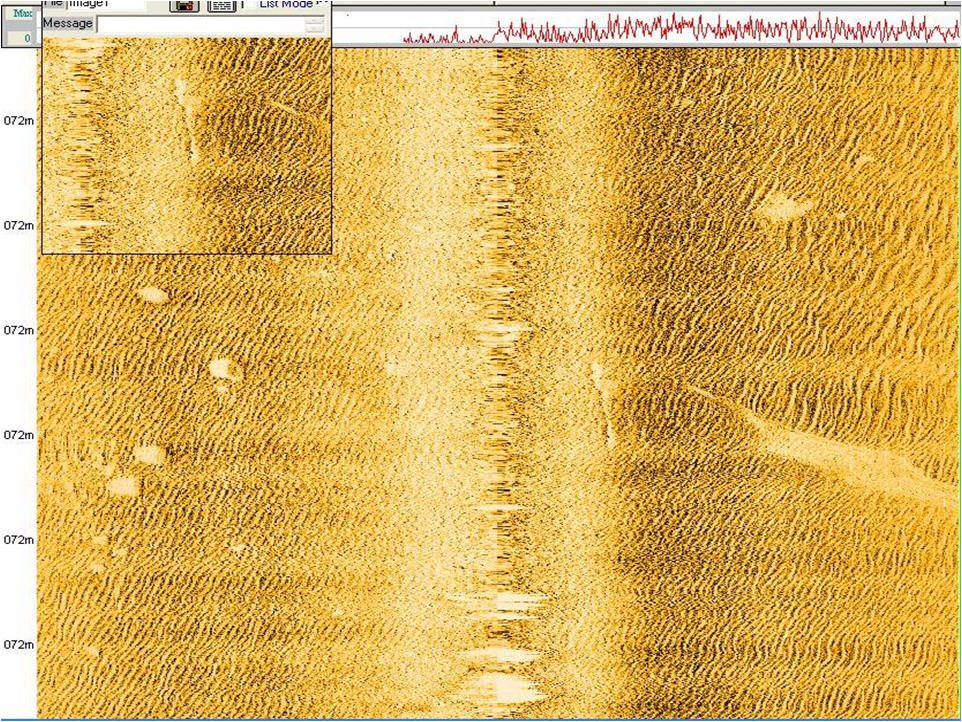

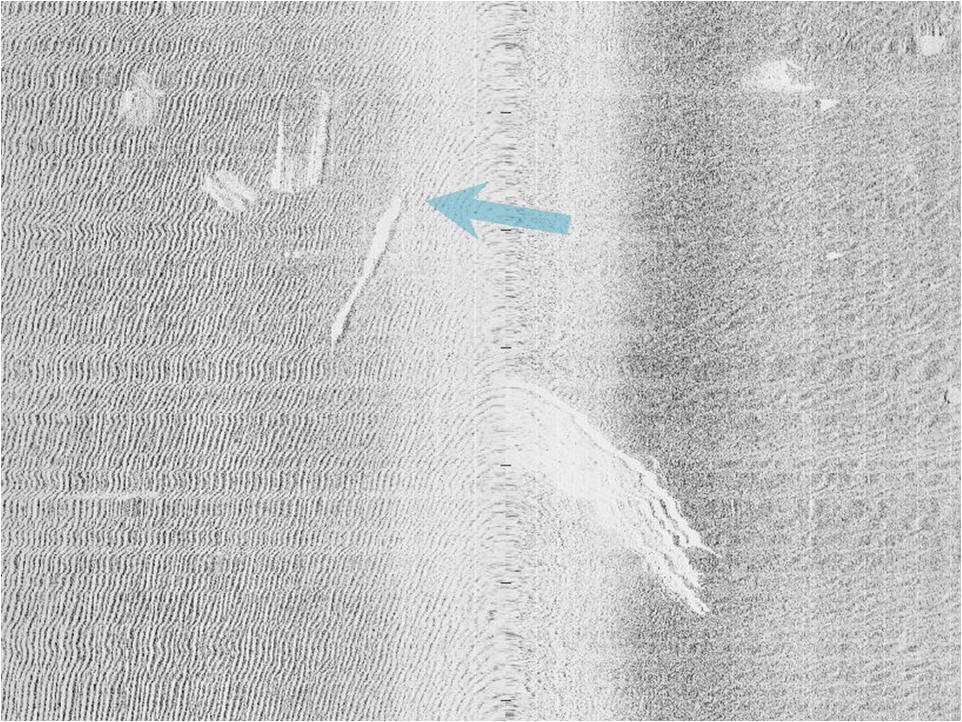

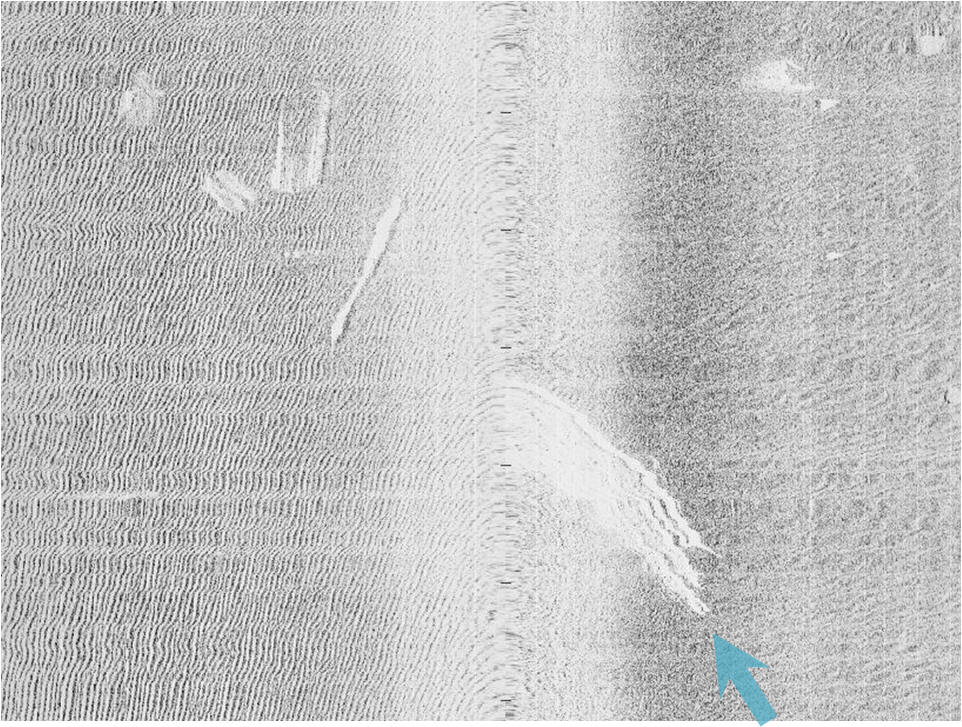

On October 14th, 2006 at 3:11 in the afternoon this sonogram was acquired using the 100kHz towfish on a 100 Meter range. I initially cataloged it as a target, but not our target of interest.

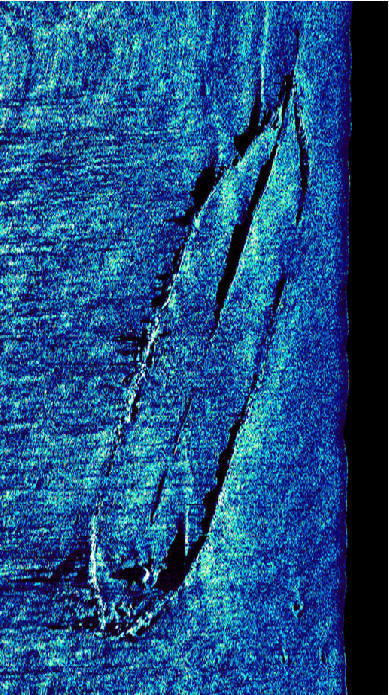

A nagging voice in the back of my head had us back out there on June 16th, 2007 re-imaging the site with the 500kHz towfish at a slightly shorter range. Although something of interest, I filed it away for a future site to dive on.

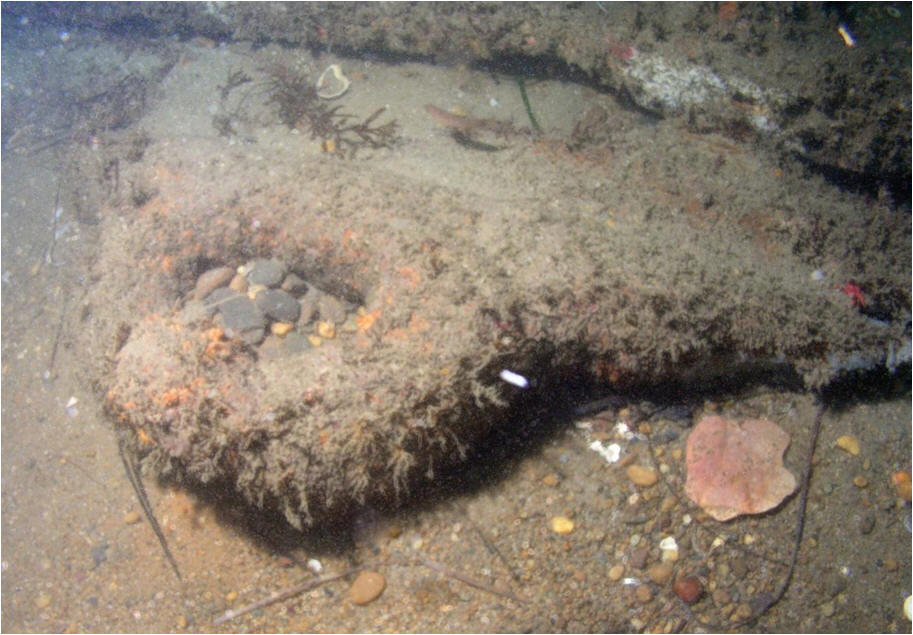

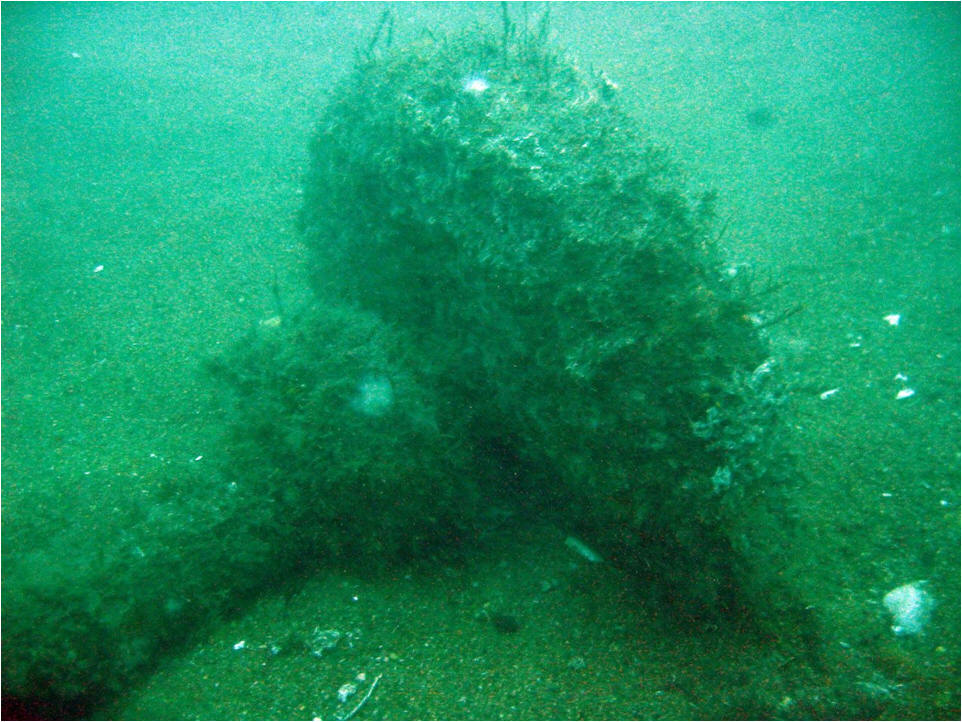

On September 22nd, 2007 Larry, a dive partner and avid JRD search supporter, asked me what I wanted to do in between dives. The nagging in the back of my head about the target mentioned above surfaced again. I decided to do a dive on it and see what was there. Larry and I suited up, a buoy was dropped on the target, and Larry and I descended to the bottom. Larry was on the bottom first and as I reached the bottom I saw him next to the object to the left with his arms out stretched as saying “ta da”, here it is.

We believe the object is either a hoisting engine or Adair (bilge) pump.

In this more detailed sonar record of the wreck site, the arrow is pointing to the Hyde Hoisting Engine/ Adair pump.

The next area we explored is a rather long straight object.

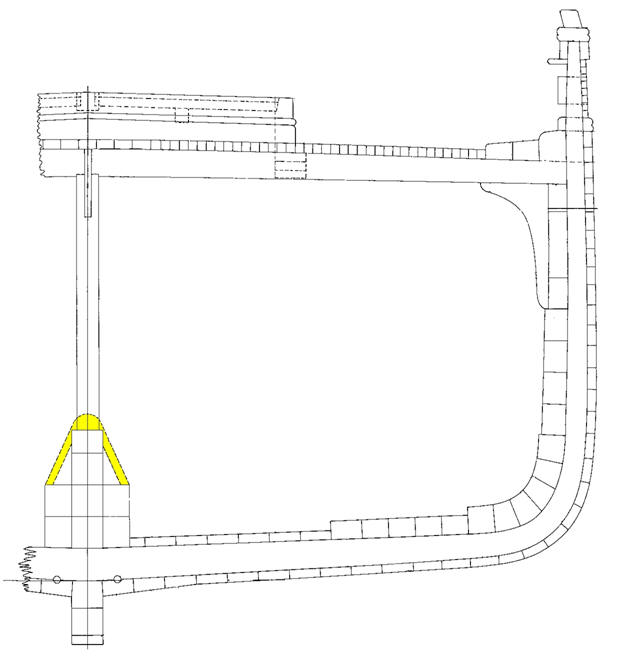

Looking at one end we see it has a very “triangular” look and the wood is sheathed in steel.

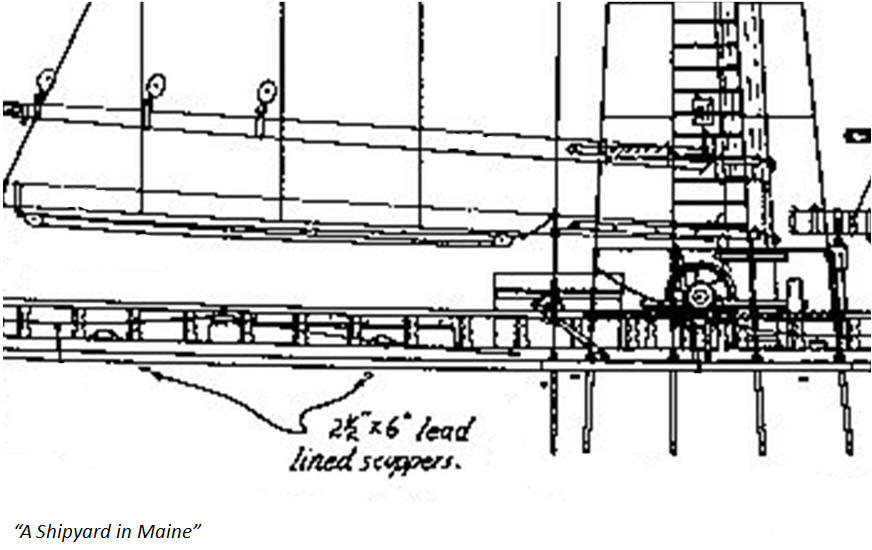

Researching the Book “A Shipyard in Maine” it was found that coal schooners protected their keelsons below the loading hatches by sheathing the keelson in steel.

As the coal was loaded from rail cars elevated above the schooner, the steel sheathing would protect the keelson from being slowly eroded away by the constant pounding of the coal.

Moving farther along on the wreck we came upon part of the main hull.

Moving farther along on the wreck we came upon part of the main hull.

We knew we were on a hull section due to the presence of ribs.

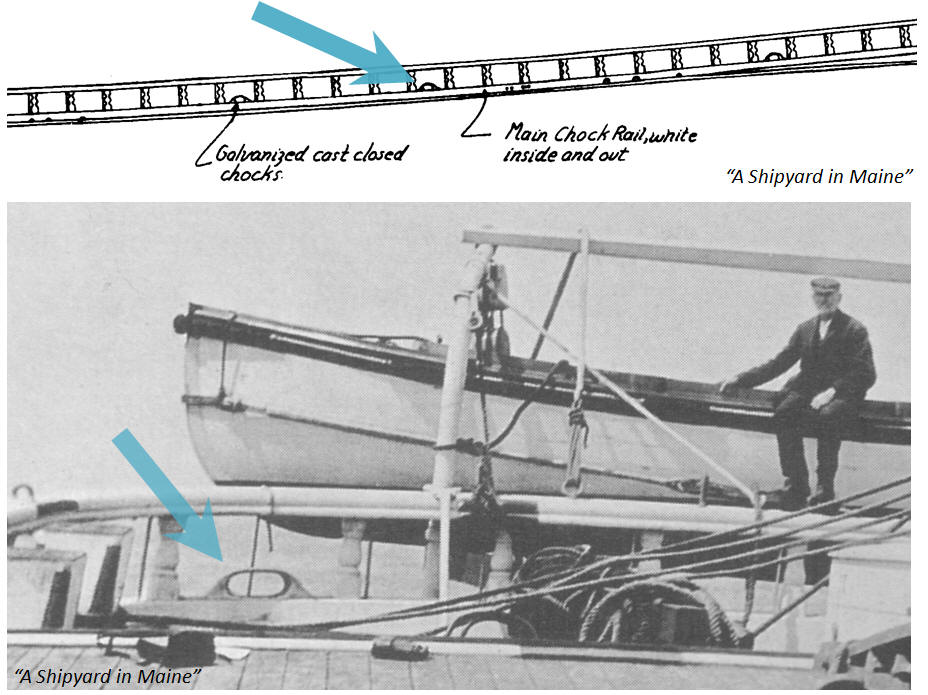

The next section we investigated was along what would have been the gunnel, or chock rail, of the schooner. Traveling from the blue arrow above to the upper left.

The next section we investigated was along what would have been the gunnel, or chock rail, of the schooner. Traveling from the blue arrow above to the upper left. On this section of the hull we found a number of closed chock’s.

On this section of the hull we found a number of closed chock’s.

We also saw what we believe to be lead lined scuppers.

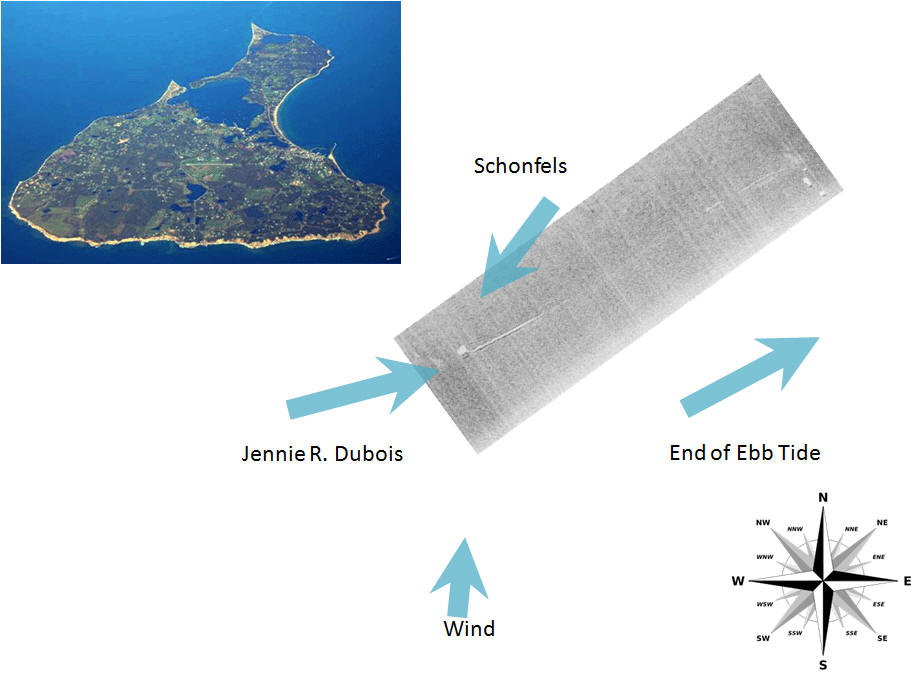

This composite sonar record shows the primary wreck site of the Jennie R. Dubois, but the question remains why does it not look like what we expected to find. We were expecting to find a typical schooner wreck like the one shown to the right. Also, where’s the rest of the wreck?

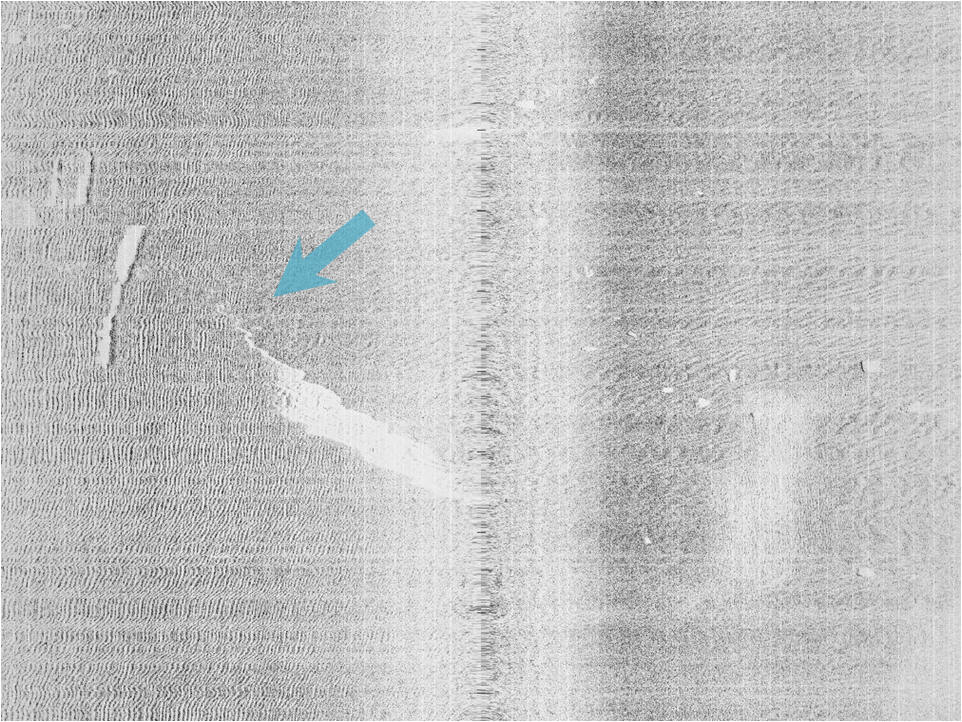

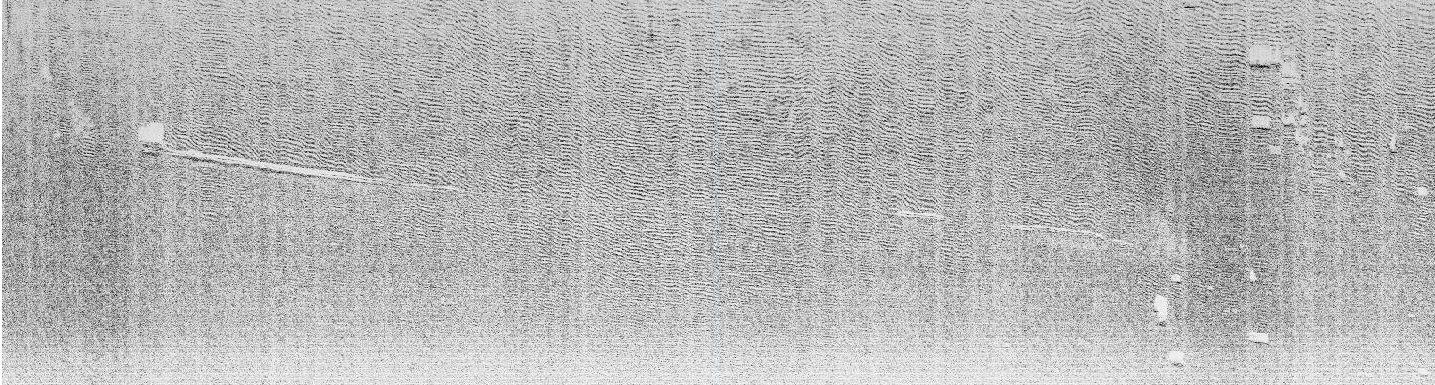

I went back and looked at my old sonar data in an area I’d covered close to where we found the main wreckage to see if I’d missed something. In the sonar record above we see a straight line going through the middle of the record. Anytime you see straight lines you should be curious. Nature typically doesn’t keep things nice and straight. I’d annotated this on the original sonar record as “something” but since it didn’t look like a schooner we didn’t investigate it any further. Well it was time to take a look.

Here is a high resolution sonar record of the straight line shown in the previous record. From end to end it’s about 600′ long and to the left we see a large mass at the end of the line. It’s going to take a dive to see what’s there. We jumped on the target to the left to investigate.

What we found was a large stockless anchor, still in it’s hawse pipe, and…

600′ of anchor chain.

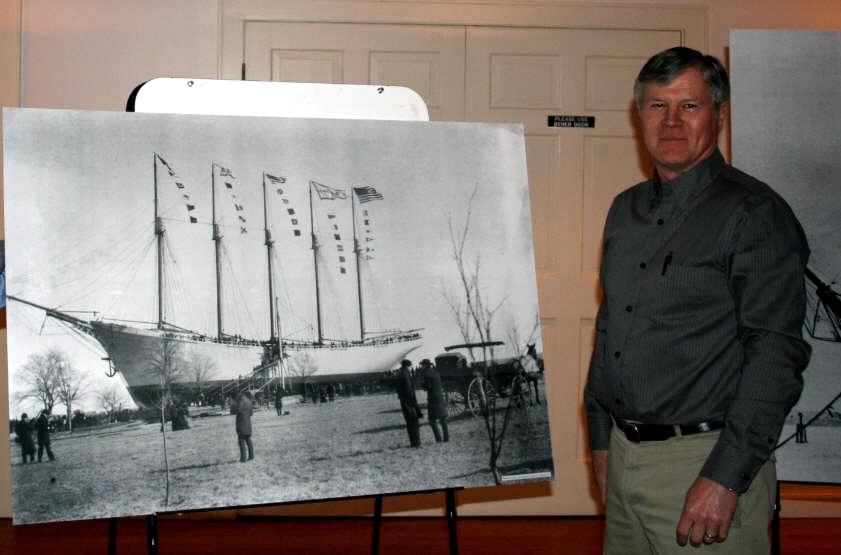

Here we see the two anchors hanging from the bow of the JRD.

And the stockless anchor

Looking at the Jennie R. Dubois we see that the there are ‘two” masts combined to make one, a main mast and a top mast.

Here we see that the top mast and main mast are held together by “Mast Trucks”. This is what we see in the above video and it starts to put some pieces of the puzzle together for us.

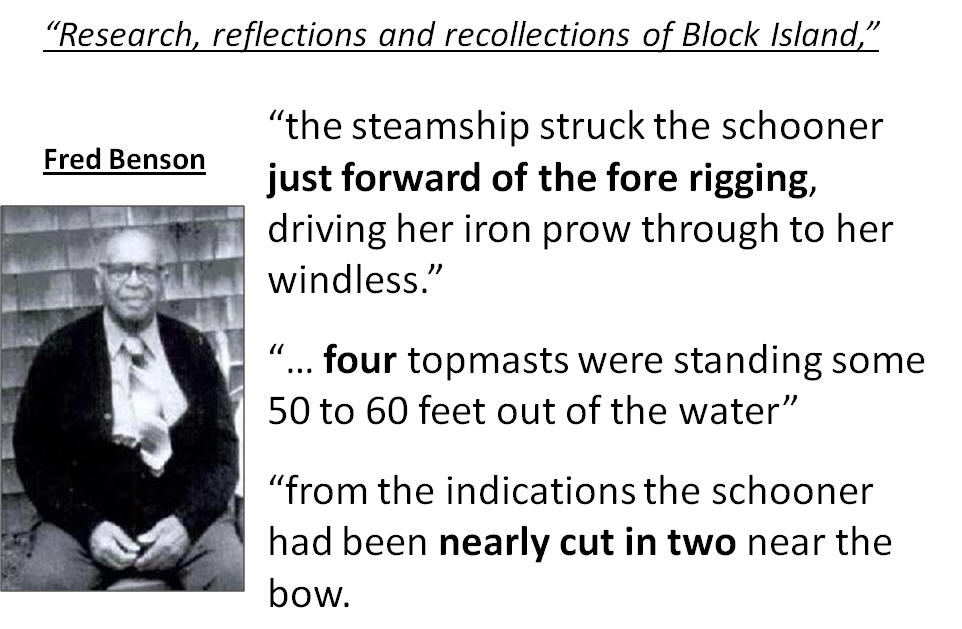

In all the research done on the sinking of the JRD Fred Bensons account appears to be the most accurate. Looking at the account of what happened during the collision and putting the story together that the wreck site’s tell we start to get an idea of what probably really happened.

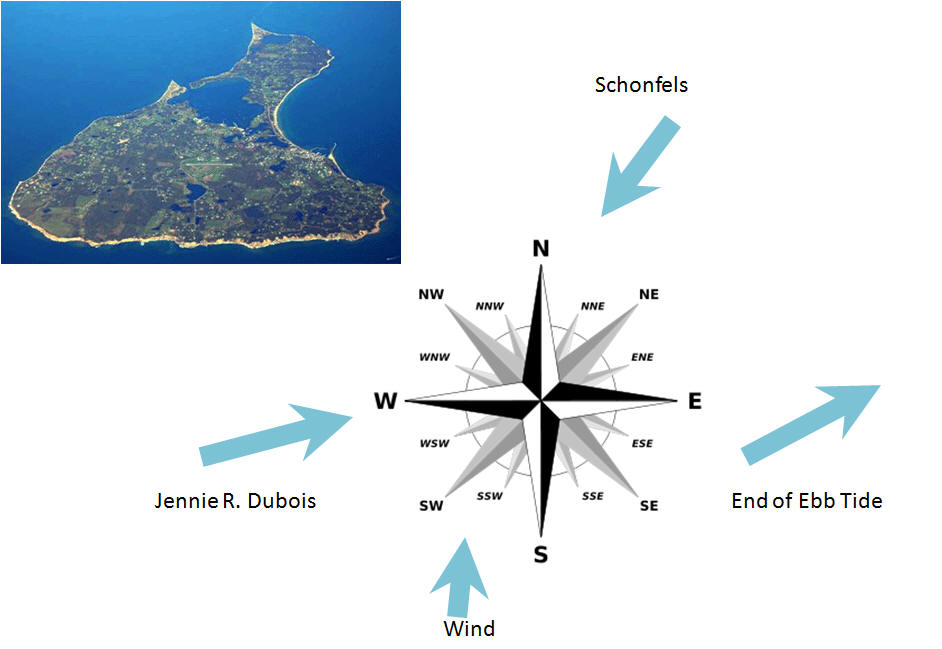

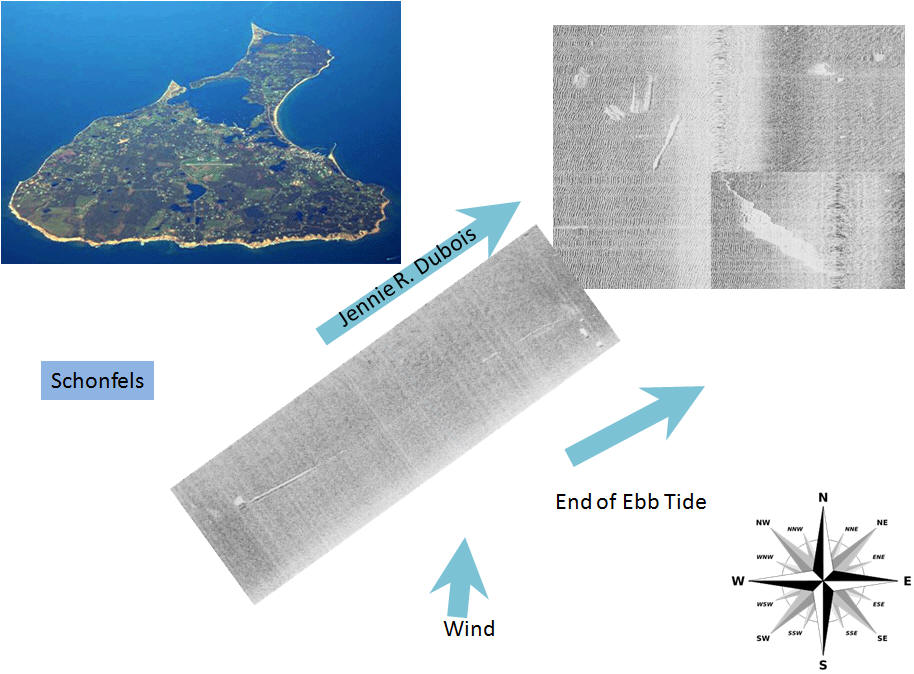

In all the research done on the sinking of the JRD Fred Bensons account appears to be the most accurate. Looking at the account of what happened during the collision and putting the story together that the wreck site’s tell we start to get an idea of what probably really happened. The JRD was heading ENE around the southeast corner of Block Island, the steamer Schonfels was headed southwest. The fog was coming in and out, at times Montauk and Block Island were in sight. The crew of the JRD saw the Schonfels and realized a collision was possible but having the right of way and not wanting to create confusion or break the rules of the road by altering course they maintained their course.

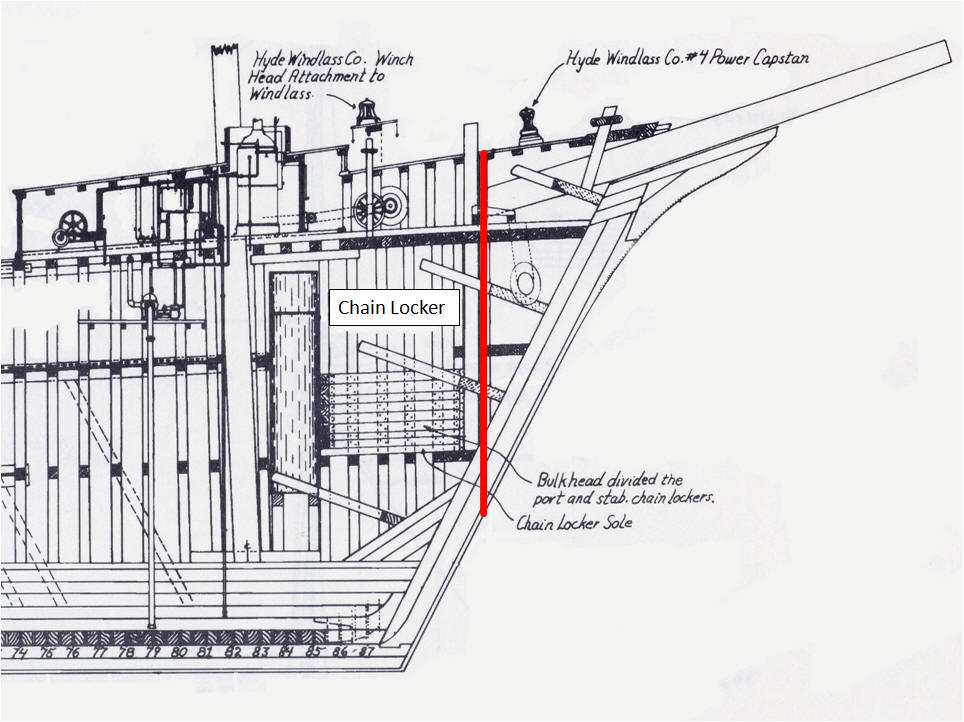

The JRD was heading ENE around the southeast corner of Block Island, the steamer Schonfels was headed southwest. The fog was coming in and out, at times Montauk and Block Island were in sight. The crew of the JRD saw the Schonfels and realized a collision was possible but having the right of way and not wanting to create confusion or break the rules of the road by altering course they maintained their course. Ultimately the Schonfels strikes the JRD just aft of the hawse pipe and forward of the bulkhead of the anchor chain locker.

Ultimately the Schonfels strikes the JRD just aft of the hawse pipe and forward of the bulkhead of the anchor chain locker.

The forward section of the bow, bow sprit, and two anchors separate from the main hull. The bow sprit is attached to the foremast by stays and the weight of the anchors and hull snaps the foremast and pulls it down to the bottom.

The JRD drifts to the ENE with the wind and tide, the anchor chain all the while coming out of the chain locker and being deposited on the bottom. When there’s no more chain left (100 fathoms or 600 feet) the bitter end comes out of the chain locker and goes to the bottom.

The JRD drifts to the ENE with the wind and tide, the anchor chain all the while coming out of the chain locker and being deposited on the bottom. When there’s no more chain left (100 fathoms or 600 feet) the bitter end comes out of the chain locker and goes to the bottom. Ultimately the JRD fills with water and sinks to the bottom herself. The anchor chain pointing in the direction of her final resting place.

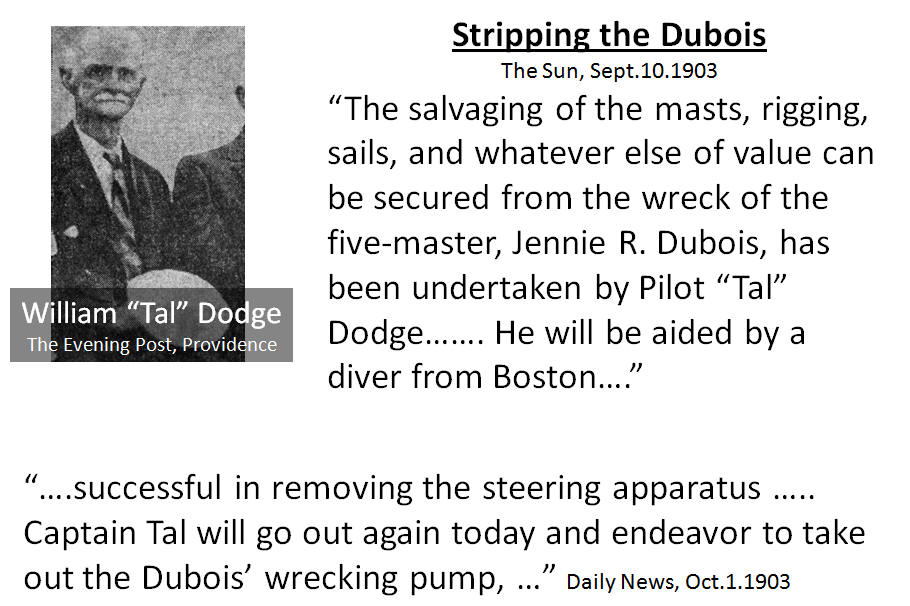

Ultimately the JRD fills with water and sinks to the bottom herself. The anchor chain pointing in the direction of her final resting place. There was no large machinery found on the main wreck site and as seen above this can be attributed to the resourcefulness of Captain Tal Dodge of Block Island.

There was no large machinery found on the main wreck site and as seen above this can be attributed to the resourcefulness of Captain Tal Dodge of Block Island.

The above description of the navy’s effort to remove the JRD as a “menace to navigation” explains the reason behind her disjointed condition on the bottom..

The A-team, those who make it all happen.

From left to right

From left to right

Larry Lawrence, John Stanford, Mark Munro, Jack Fiora, Scott Annis, Jeff Godfrey, Mike Fiora, Joe Mangiafico

I’d just like to give a special thanks to Larry for his undying support of ALL my projects, he’s been there through it all from the very beginning. Without his persistence and pushing me to excel I know we wouldn’t have come as far as we have.

Thanks Larry!

A view of Block Island while over the wreck of the Jennie R. Dubois

A view of Block Island while over the wreck of the Jennie R. Dubois